July 2019, Bake #4: Sourdough

July 21, 2019

It has been a long time coming, but I finally made some sourdough. Some real, honest-to-goodness San Francisco sourdough! It is almost like I am like a real-life baker!

Start with the starter

I got my sourdough starter several weeks ago, on a weekend trip my wife and I took up to Sonoma. We were exploring the area and stumbled upon a quaint little bakery called Wild Flour Bread in Freestone, California. I think we only stopped for a coffee and scone, but after seeing their offerings I was compelled to buy not just one, but TWO loaves.

I also had the foresight to realize I would eventually be baking some sourdough as part of this little baking adventure of mine. So I asked if I could buy any starter from them. I asked this question sheepishly, concerned that it would be seen as an Extremely Weird And Dumb Thing To Ask, as if I were to stroll into Coca-Cola HQ in Atlanta and ask the receptionist to quickly jot down the Secret Formula for Coke on a notepad for me.

But the person behind the counter at Wild Flour didn’t bat an eye. He said it would cost five dollars, and did I had a container to put the starter into? I did not. So they schlepped some into a paper coffee cup and let me on my merry way.

FEED ME

If you are unfamiliar with sourdough starter, I will describe it for you:

Sourdough starter is the paradigmatic goop.* It is an active yeast culture, and so it must be tended and fed on a regular basis. Feeding should occur every eight to twelve hours, unless the starter is kept cool in the fridge in which case you can get by feeding it only once a week. To feed the starter you mix equal parts starter, flour, and water, measured by weight. (I usually do 50g of each.) Since you are always adding new mass to the starter, it is continually expanding. This means there are thousands (if not millions) of ballooning sourdough boluses in bakeries and homes across the planet, silently growing, eternally feeding, nourinshed by their caretakers, those unwitting priests of a doughy doomsday cult; and one day these starters will so swell in size that they will topple their containers, pouring out into the streets, gliding across interstates, consuming towns, toppling forests, absorbing oceans, until they eventually join into a single terrible Unity that subsumes the Earth, a living planetary blob, and all that will be left of our species and of this whole grand human experiement is a writhing, pulsing, hungering cosmic orb.

But in the meantime, we get to enjoy ourselves some sourdough!

From wet to dry

The first step in my bread book is to take some of the wet barm and mix it up into a dry starter. I guess the idea here is that it’s easier to feed and maintain a barm containing a high proportion of water, but once you actually want to make some bread you need to up the amount of flour so that the little yeastos† really start acting up and start nomming on all the tasty tasty starches.

According to my book, the truly passionate pros maintain their starter in this dry form at all times, bypassing the wet barm altogether, so that they are ready at a moment’s notice to make some bread in the case of a SOURDOUGH EMERGENCY. Let us all take a moment to thank these consummate professionals; who among us have not been saved in a moment of crisis by the quick arrival of an EST?‡

But since I am not a consummate professional, I had to make a dry starter. This is not a difficult process, but it is a time-consuming one, since there’s a lot of waiting around for the yeastos to either (1) warm up after being in the fridge overnight, or (2) munch munch munch away at some flour. I don’t have many meaningful notes about the process, other than to say that next time around I should be assiduous about documenting my process: my bread ultimately turned out pretty good, but I don’t have any way to recreate it since I don’t remember how long I waited for stuff to ferment and I didn’t take any photographs of the in-progress starter.

Kneading the dough

The first step in making the dough proper was to take my blob of dry starter out of the fridge, chop it into ten smaller slices, and wait for it to warm up. I actually did take a picture of this step!

I mixed everything up in my big ol’ glass bowl until it was sufficiently blobby that I could dump it onto the counter to start kneading. I wish I were O.G.** enough to do the bowlless approach, where you pile up the flour on the counter and make a little crater in the middle that you pour the wet ingredients into and then you mix everything together by hand. But I am not yet enough of an O.G. to be able to do such a thing.

As I have mentioned in previous posts, I enjoy kneading. This dough required more kneading than anything I’ve made to date, approx. 15 solid minutes of kneading. It was a WORKOUT. I still enjoyed the process, but I was straight BUSHED by the end of it.

Playing music while I kneaded helped, but I have decided that I need to make a Dedicated Kneading Playlist. There’s nothing worse than enthusiastically kneading along to a banger and then getting bushwhacked by, like, “He Stopped Loving Her Today” – which, while a most excellent song, isn’t really knead-friendly.

INCIDENTALLY, I just searched for “kneading” on Spotify and found:

- A podcast called “Kneading Dough”, which I got extremely excited about, but only for a moment, because then I clicked through and realized that it was a podcast about SPORTS (BLARGH, BLECH, EW).

- A playlist titled “Kneading Music”, made by someone who apparently enjoys kneading to classic rock. (Which is totally legit, no qualms here.)

- Another playlist, “Sonic Kneading”, whose compiler seems to prefer more of an electronic poppy sound. (I think this is slightly more my style.)

- A third playlist, titled “kneading”, probably the most eclectic of the bunch, and also very good.

What I have discovered is that kneading playlists are universally excellent (three shots, three hits!) and probably everyone should make one. I will link to my own in a future installment of this journal. (Maybe.)

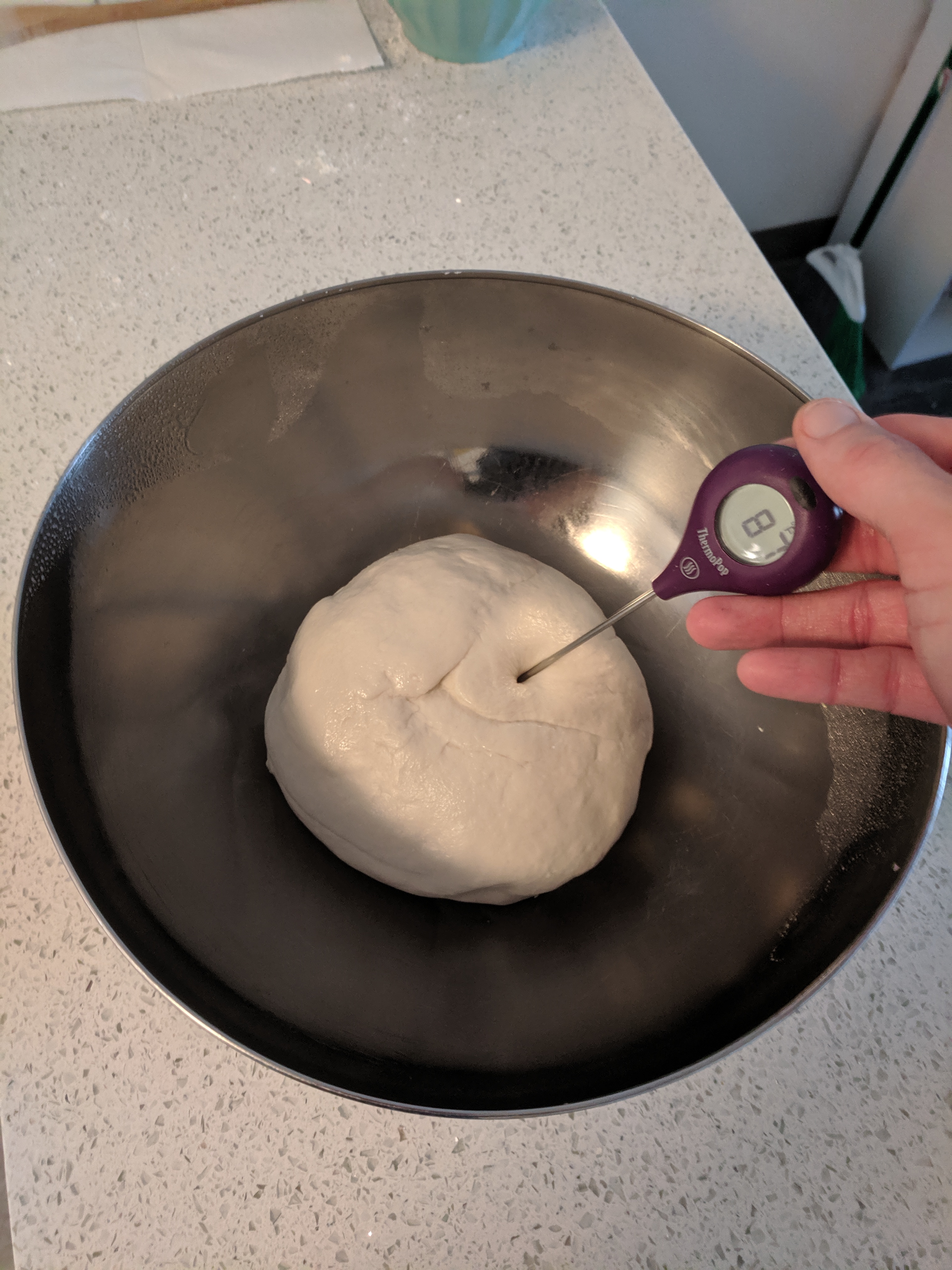

My bread book said I should knead until the dough passed the windowpane test and registered 78º–81º.

As you can see, my own dough was warmer than recommended. I don’t know if it makes a big difference; I’ve looked it up, and it seems like baker’s yeast is most active in the 85º–95º range – so it kinda seems like my bread book’s recommendation is too cold?? But maybe they have another reason for suggesting that specific temperature range???? Who knows!!!!! ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Fermenting and shaping and proofing

I don’t have any photos of the process, but at this point I let the dough ferment in a bowl for several hours (or until it doubled in size). At which point I divided the dough and shaped the final loaves into boules.

I like boules because they are simple to make and they look so nice when they come out of the oven. They’re not fancy nice, but they turn out as beautiful orbs that are weirdly mesmerizing. I definitely like boules more than bâtards, which in my opinion are kind of goofy-looking; and baguettes, which whenever I’ve tried making them have turned out sad and short and stumpy. It’s possible that if I got better at making baguettes I would like them more. It’s also possible that if I got better at lion-taming or winning the lottery I would like those things more, too.

That said, I should really try some fancier shapes, like a couronne or an épi cut. Trying a couronne would be an excellent excuse for me to purchase a ringed brotform, which is a fancy term that means “entirely unnecessary basket that looks kind of like a sombrero and is only useful for making couronne breads and literally nothing else”. (Indeed, it is such a use-case specific piece of baking equipment that I am having trouble finding places other than German-language websites to purchase one.)

Anyway, after shaping the bread, I shoved the loaves straight into the fridge and let them retard overnight.

In general, it’s been like a Whole Big Thing every time I try to bake something. At this point in my baking education, I am beginning to think more about matters like Procedural Efficiency and Fitting Baking Into My Everyday Life. I’d like to streamline the process a bit so that I can, say, make bread without giving over an entire Saturday to the process.

In the case of this sourdough, I ended up making it over the course of three days: dry starter on the first, dough on the second, and bake on the third. I like this process, because each day involves a relatively small commitment of time and dirty dishes. I could see myself doing this over the course of a few weekdays, rather than having it be a big weekend commitment.

Baking the bread, finally!!!

I took the loaves out of the fridge approx. four hours before baking them, to let them rise a little while longer. This bread didn’t rise as much as other loaves I’ve made, which got me a little worried about the health of my sourdough starter. Was it even alive? Was I trying to make bread with sickly little yeastos?

But I had come too far to give up now! I let the final proof go on for as long as possible before I really needed to pop my loaves into the oven if I was going to get to bed at a reasonable hour.

In the final few minutes before the bake, I scored the bread with a pair of recently-purchased Japanese scissors. I used a highly advanced upward-pulling snipping motion that I have dubbed – due to the speed, grace, and delicacy of the movement involved – the “Ginger Hummingbird Technique”. I unfortunately cannot really describe the technique in words, but I can tell you that my loving wife oversaw the entire scoring process and was greatly impressed with it. She definitely did not laugh at me at all, not even once.

For the actual bake, I did the whole hearth baking thing. There was a good bit of oven spring, so that by the time the loaves came out they were of decent size. Smaller than pretty much any other loaf of bread I’ve made, sure … but not bad.

I was also happy to find that a decent crust had developed, to the extent that I had some trouble poking my thermometer into the bread for a final internal temperature reading. Historically I’ve found that, even when I do the hearth baking thing, the crust doesn’t get nearly as beautiful and, well, crusty as I would like it to.

Final verdict

The sourdough came out with a pretty decent tang!†† I really don’t have many complaints: this was a tasty bread that wasn’t too tough to make. I think for my next rodeo I’ll try out a variation, maybe a sunflower rye or even a pumpernickel.

* I dunno, maybe there is a more paradigmatic goop out there. But starter has a lot going for it:

-

It’s quite viscous and sticky – but not TOO viscous and sticky.

-

It has a bland, pasty appearance, like glue.

-

It is ALIVE.

For these reasons, it beats out simple goops like honey (too viscous; not alive), snot (too variable in its viscosity; also not alive), and spectral ectoplasm (definitely not alive; also, not real).

There’s a case to be made for slimy molds – e.g., what grows on baby carrots when they’ve been sitting in the fridge too long – as being even MORE paradigmatically goopy. Specifically, slimy mold is translucent in a way that really captures the platonic essence of goop, in a way that sourdough starter’s doughiness simply doesn’t.

But mold is SUPER GROSS so I don’t want to think about it anymore.

† This is how I lovingly refer to the single-celled organisms that comprise baker’s yeast. Their technical name is, of course, yeastoid.

‡ Emergency Sourdough Technician

** Fun fact: O.G. stands for officium glutini, or “Officer of Gluten”, a term originating in the Roman military.

O.G.s were the bakers who were in charge of feeding the Roman legions during their long campaigns. Although O.G.s rarely saw battle (and despite the fact that they were almost invariably captured slaves who had been pressed into Roman military service) these men still commanded great respect and prestige amongst rank-and-file Roman troops, as they had the highly visible and popular responsibility of feeding the troops on a daily basis.*** Furthermore, because O.G.s rarely engaged the enemy directly, they tended to live and serve longer than nearly any other member of the army. By the time of the Late Roman Empire, O.G.s had developed a reputation for having been on many more campaigns than the average man; and their popularity was such that it became convention to reward these slaves with their freedom after 30 years of honorable service. In their veteran lives, O.G.s often became itinerant storytellers, regaling audiences with their (generally exaggerated) tales of war. Although rarely literate, a handful of O.G.s did manage to record their stories for posterity, and in fact most of our knowledge of the Late Roman military come from men like Calvus Brodinius, Rusius Tirennian Jonius, and Erillius Simonus the Elder.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the ancient title of O.G. found its way into use among various European courts. Initially it was used as a term of respect for so-called “men of the oven”, but this meaning quickly attenuated to what was essentially a ceremonial title, mainly used to designate the ruler’s most senior advisor or some other position of elderly respect. By the time of the absolute monarchs of the 17th century the term fallen out of use, and in the few courts where it did find use it had been entirely stripped of its original meaning.

The term’s renewed popularity in modern times is almost entirely thanks to the actor and rapper Ice-T, who titled his 1991 album O.G. Original Gangster, a tongue-in-cheek spurious etymology that has since gained traction has the true meaning of the term. This is especially ironic, given Ice-T’s reputation as a rather serious amateur historian and classical philologist (he famously co-authored a piece in Antichthon with Mary Beard); he is on record as being frustrated at how his joke unintentionally caused such a widely accepted misapprehension, and that he wishes more people would take the time to familiarize themselves with the true history of the term.

†† This is the so-called “Deece Tang” for which San Francisco is famed, and why the San Francisco Giants are lovingly referred to as the “Deece Tangos” by their fans.

*** Not to mention that getting on the bad side of an O.G. could lead to undersized meals, bread loaves spiked with sawdust, or any other number of unpleasant culinary consequences – whence the O.G. corps’ unofficial motto: non personalem, sic est negotium.